The first book I was ever paid for writing–back in 1976 or ‘77—was a ludicrously bad historical romance written pseudonymously for a third-rate paperback publisher. Everything about the project, from the advance to the production values of the finished book, was low-rent and small-time. Still, I learned a few things from the process—mainly about the discipline and resourcefulness required to write in genres that have rules.

Rule one in writing historical romances was that the books had to be at least 100,000 words long; readers wanted some heft for their $1.99. The second rule was that the action needed to be set against a backdrop of epochal events so that readers, tragically, could imagine that they were actually learning something. (My book, as well as I can recall, opened with a skirmish in the French Revolution, moved on to a Virginia plantation, and found its merciful conclusion in a midwestern homestead.)

But by far the most interesting rule had to do with the character of the heroine: She had to be sexy but chaste. She needed to be beautiful, of course, but describing her beauty was merely filler. The crucial thing was that men desired her. Sometimes these were nasty men who plotted to take her by guile or force; sometimes they were kind and wealthy men whose only fault was that the heroine didn’t love them. In any case, she could not yield to their advances. Not that she wasn’t tempted, mind you. She was certainly aware of sexual stirrings in her own mind and body, however daintily these needed to be expressed. No fool, she certainly understood that accepting an older, prosperous suitor could make her life a great deal easier. But it was an absolute requirement of the genre that, however many close calls she might have endured in the course of 100,000 words, she preserve her virginity until being passionately conjoined, at the very end of the story, with her one true love.

Having a long book to write and a six-week deadline in which to write it—on a typewriter, no less–I didn’t think much about the morality or psychology of this last rule. I just followed it. But I’ve come to believe that, in storytelling terms, at least, there must be a compelling and durable wisdom in that genre convention, because, two decades later, in a completely different sort of book, I found myself being guided by it once again.

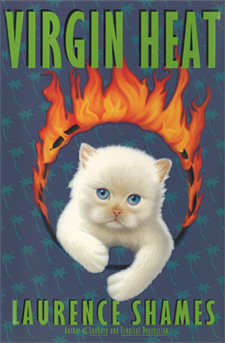

Virgin Heat, the fifth of my Key West novels, is built around the character of Angelina Amaro, the gorgeous daughter of a New York Mafia don, whose life had essentially stopped at 17, when her boyfriend disappeared. Without giving away too much plot: He disappeared into the Witness Protection Program, and he had to go there because he’d ratted out Angelina’s father. When, years later, the boyfriend/stool pigeon resurfaces—in Key West, where else?—both father and daughter desperately want to find him. The father wants to whack him and the daughter wants to take him to bed to finish what they’d started so long before in the back seat of a car.

Confusions ensue; subplots develop; I like to think that comedy happens. But through it all, the story stands or falls with Angelina and her loopy quest. Like nearly all romantic heroines, she is very sexy in her innocence; she’s been so wound up for so long that she can’t even sit still in a chair. The object of her affections is completely unworthy of her; the reader knows this, even if Angelina herself does not, but it really doesn’t matter. What matters is the stubborn and slightly crazy purity of her desire.

It’s this purity, I believe, this willful abstention, that makes the reader root for Angelina. Erica Jong may disagree, but it’s hard to root for a slut. I’m not proposing a double standard here; it’s also difficult to root for an inveterate male seducer. In either case, there may be some vicarious titillation or even envy in reading about the exploits of promiscuous characters, but do we actually like them? I think not. Even in a sexually permissive era, there seems to be a gut-deep belief that true love is a more admirable calling and a (relatively) surer path to happiness.

This helps to explain the appeal of the sexy-but-chaste heroine; but there is another, more practical reason why characters in novels tend to absent themselves from felicity. When people actually have sex, there is a well-known release of tension. This may be a wonderful thing on a Friday evening but it’s a disaster halfway through a book. Then what? Why should the reader keep going? What takes the place of the squandered suspense and yearning? It’s like solving the crime halfway through a murder mystery. What do you do for an encore?

So then, coming back to Virgin Heat, how long does Angelina have to wait for her catharsis? Does it ever come at all?

You don’t really expect me to reveal that, do you?