It had always been my dream to be a published novelist; so when I graduated college in 1972, I set out, with great determination and complete naivete, to become one, suffering meanwhile through a succession of the usual awful jobs to support the quest. I wrote longhand in those years, filling cheap cardboard-covered notebooks with short stories, sketches, random thoughts, and attempts at longer things. I call them “longer things” because they really don’t deserve a more specific name. If a “longer thing” filled more than, say, two notebooks I started to think of it as a novel.

It wasn’t, of course. It was just a “longer thing.” I had no idea how to write a novel and I made all the mistakes young writers make, unless they happen to be geniuses. Impressed with my own vocabulary, I used fancy words when simple ones would do. Clueless as to plot-construction, I decided that plotting was beneath me. Every “longer thing” had a hero who closely resembled me. Brooding yet clever, he hogged the good lines and won every argument.

Not to put too fine a point on it, my fiction sucked; it sucked a little less bad the more I practiced. But then, by a series of lucky breaks (I’ll save the details for another time), I began to have a career in magazine journalism, and I put fiction aside in favor of sorts of writing that people would actually read and for which I would get paid. This was a refreshing novelty…but also a compromise. And I dimly understood that compromising could get to be a nasty habit.

Cut to 1989. On the strength of no credentials whatsoever, I am offered the chance to ghost-write a nonfiction Mafia book for two FBI agents. I have no idea how to make this work, and God knows the FBI guys certainly don’t. At a terrifying meeting under bad fluorescent lights, the editor intones a few magic words: “Write it like it’s a novel. You know, just craft the story.”

Just craft the story. What a concept! In that moment I began to understand something very basic that, in my youthful hurry and romantic fantasies I had somehow overlooked. A book was an artifact. Not a confession, a rant, or a spontaneous outpouring. It was something to be worked on, something to be shaped. With that in mind, the ghosting assignment suddenly seemed…I certainly won’t say easy, but clear. I pocketed the advance, moved from New York to Key West, and wrote every single morning for half a year. The result was Boss of Bosses, which, fortunately for all concerned, went on to be a bestseller.

In the wake of that book’s success, the editor asked what I’d like to do next. Trying to sound confident and firm, I said I’d like to go back to writing fiction. There was a longish silence at the other end of the phone line. I’ve always imagined that the editor was thinking something like this: Oh, great. We’re making money with this jerk as a ghostwriter and now he imagines he’s a novelist. Well, let’s give him a dinky advance and let him try. He’ll no doubt fall on his face but it’ll keep him out of trouble until we need him for the next nonfiction gig.

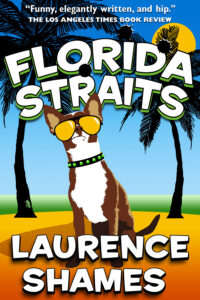

The editor asked if I had an actual idea for a novel. I told him I did, sort of. For the previous year or so I’d had two things on my mind: the New York Mafia and the hilarious quirkiness of my adopted hometown, Key West. So I wanted to write a story about a young, very un-tough Mafia misfit who goes to Florida to reinvent himself and, by virtue of smarts and courage he never knew he had, ends up muddling through to a better life.

This was the kernel of Florida Straits. Without doubt, it was to be a very personal book. In describing Joey Goldman’s first impressions of Key West, I borrowed heavily from my own; the compound where he lives was drawn stroke by stroke from my own first Key West residence. I’d eaten fish sandwiches at the same bars where Joey eats them; I’d watched sunsets from the exact same swaths of sand. But at the same time, there was a healthy distance between me and my protagonist. His Dad, after all, was the Godfather, whereas my old man sold furniture and was, for better and worse, actually married to my mother.

What all this added up to was that, probably for the first time in my attempts at fiction, I was using what I knew without writing about myself. A fine line there, but a crucial one. The distance let me see more clearly the kind of story I hoped to craft—a sort of fish-out-of-water, coming-of-age, caper-romantic-comedy hybrid.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the publication of Florida Straits. More by coincidence than planning, it is also the first time the book is available in e-form. It means a lot to me to keep the title available. Like every author, I hope to reach new readers every day; but it tickles me, as well, to imagine that there may be folks who read the novel years ago and might like to revisit Joey, Sandra, Bert the Shirt, and the chihuahua, Don Giovanni, as old friends. As for me, I check in on them regularly and am pleased to report that they are all well and happy.