Some authors set down detailed and scrupulous outlines of their novels before they write a single word. The case can be made that this is a good idea but I don’t do it. I just start. There are two reasons for this approach. First, I’m not smart enough to know much about the story I’m writing until I get immersed in it. Second, I like to be surprised at least as much as the reader does, and an outline murders the suspense. Writing a novel takes me most of a year. That’s a long ballgame to sit through if you already know what happens every inning. So I prefer to wing it.

Winging it, of course, is not without its dangers. Every writer—especially but not only in first drafts–makes mistakes: false starts, wrong turns, motivations that don’t quite add up, the occasional scene that sits there dead on the page. These mistakes take time to make and time to correct. But is this wasted time? I like to think it isn’t. Readers will never see the parts of novels that have been rewritten or expunged—but the author knows that they were there, and this lends texture.

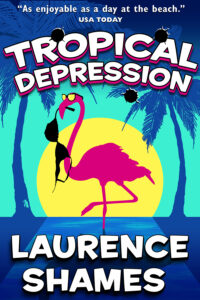

Consider an example from Tropical Depression, the fourth of my Key West novels. When I started writing that book, all I knew about it was that it featured a depressed lingerie executive—Murray Zemelman, aka The Bra King—who had made a mess of his New York life by dumping his wise and steadying wife in favor of an airheaded trophy bride. Desperate, he flees to Key West to reinvent himself and try to make things right. Complications ensue (largely revolving around a scheme to launch an Indian casino in spite of strong objections by corrupt legislators in league with the Mafia. But let’s leave that on the side for now).

In any case, I started writing the book and something just wasn’t working. I know when something isn’t working because it makes me itch and fidget and want to jump up from the desk and scream. So after twenty or so pages I showed the manuscript to my agent. To him the problem was obvious.

“Your stuff is supposed to be funny. This is about a depressed guy. Depressed guys aren’t funny. They’re…well, depressing.”

“Right,” I said. “But he’s only depressed for a while. Then the Prozac kicks in and he gets manic. Manic is funny, right?”

“Manic can be funny,” he allowed. “But this miracle transformation, when does it happen?”

“Soon. Like page 25 or 30.”

“Needs to happen sooner.”

“How much sooner can it happen?”

“How about page one? He’s depressed for, like, three paragraphs. That’s plenty. Try it.”

So, not without resistance, I did. Out went 20 pages of misery—droll misery but misery nonetheless. The book now opened with what I frankly consider a hilarious suicide attempt. (Call me sick, but I happen to believe that a suicide attempt can be extremely funny as long as it’s botched.) Murray is sitting in his closed garage with his engine running. Just as he’s on the cusp of losing consciousness, his depression lifts, he skips straight past normal and into the manic phase. Hungry for life, he throws the car into reverse and crashes through the garage door into daylight. He’s upbeat if not berserk for the rest of the book.

But here’s the thing. If I hadn’t put Murray (and myself) through the grumps and tribulations of those first 20 thrown-away pages, I would have known a lot less about him. I wouldn’t have known how hard he’d worked to earn his (relative) happiness, to rediscover his zest for things. For Murray, becoming a bold and open-hearted goofball is a kind of existential triumph. Triumph over what? The reader doesn’t need to know that in excruciating detail, but I think it’s helpful that I did. To me, knowing a bit more of what Murray had recently been through makes him both more sympathetic…and funnier. I see him shining through his very own darkness, and I hope the reader senses that as well.